I have often wondered why museums and galleries don’t offer regular food programs. And why don’t art schools offer degrees in food preparation? If they did, the Danish artist and writer Kasper Hesselbjerg would be a program director or a regular visiting artist. Take his 2021 book, Recipe for Snails and Success, produced with the Art Sonje Center in Korea. It extolls the virtues of snails. You can use their mucus as a skin treatment. If you cook them poorly, though, they can lose their flavor. Still, a dish of snails cooked correctly, in Hesselbjerg’s estimation, is delicious. Yet, nowhere in his recipe does he share any measurements. Perhaps without prescribed teaspoon and cup counts, your problem-solving skills will kick in, and you will even let your own aesthetic wildness into the somewhat structured experience of Hesselbjerg’s memorable, narrative recipe. Put snails in a vegetable soup along with root vegetables, ginseng, ginger, goji berries, dates, bay leaves, star anise, and thyme. After the soup, get the snails back into their shells, then into the oven. As a flourish, the artist-chef recommends covering the opening of the snail shells with gold leaf, which is edible and relatively cheap. He asserts that consuming the snails with gold leaf “expresses a magnificent decadence and immoderation, causing the serving of snails to exceed even oysters in status and symbolic value.”

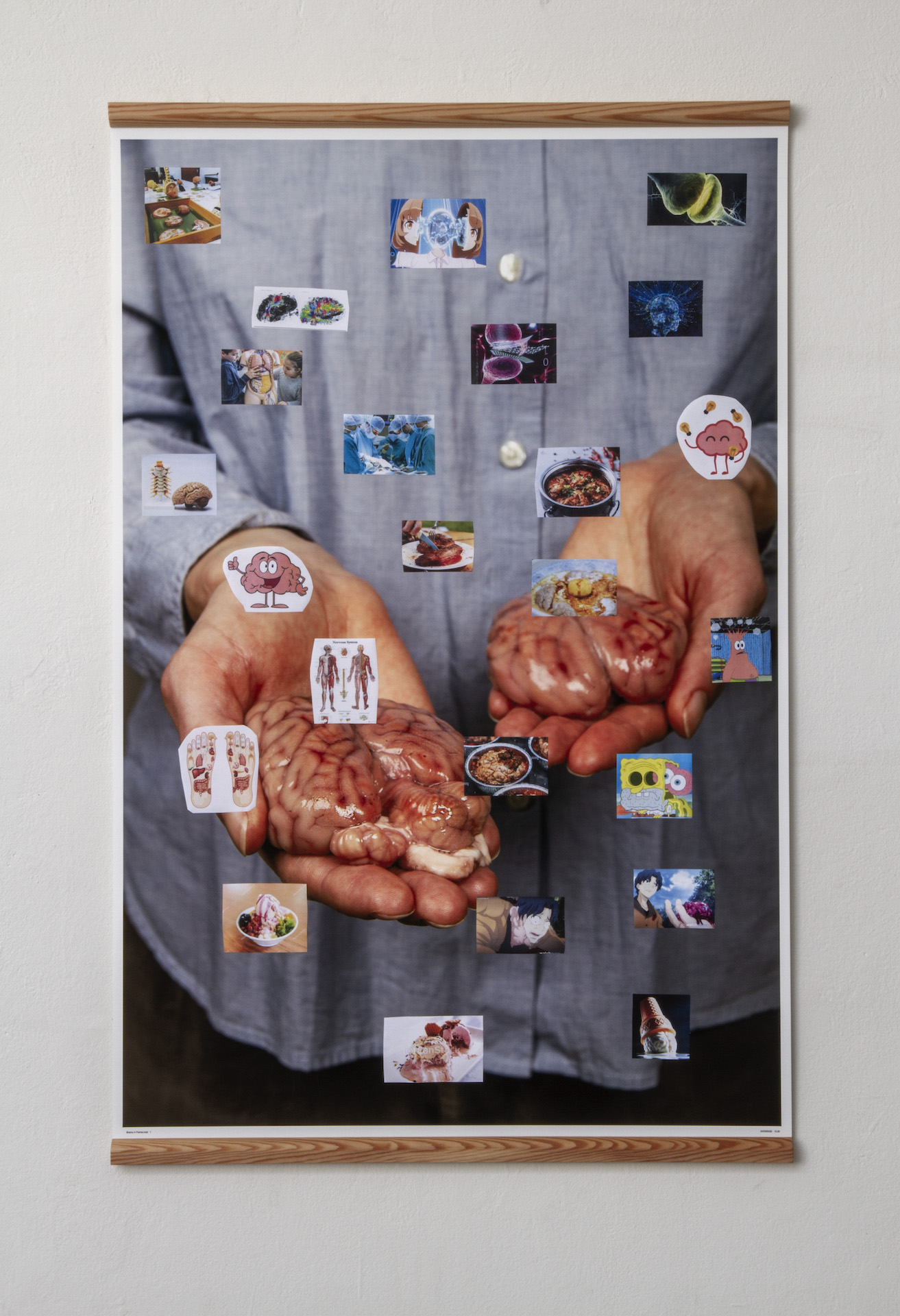

In addition to making books, Hesselbjerg has mounted solo exhibitions in Copenhagen, Paris, and Beijing, and is the founder of the publishing house Emancipa(t/ss)ionsfrugten. He displays a keen sensitivity to the page. His collages on paper, in appearance, are reminiscent of some of Richard Prince’s typological works from the 1980s—grids of appropriated images of cartoons, cowboys, clouds, waves, cars, and women. Yet, the 37-year-old artist wants to give us less predictable experiences.

Considering Hesselbjerg’s work, my mind jumps to a trip I took to Pittsburgh about eight years ago. I had heard about a lunch spot serving a hamburger on two glazed doughnuts instead of a bun. My friend and I walked all over Pittsburgh to find the place. When we got there, I sat down and giddily ordered one doughnut hamburger and a beer to wash it down. After two bites, I knew I had made a mistake. The high-calorie onslaught of intense sweetness melting into bloodiness and saltiness was too much for me. The alcohol made things worse. This combination of previously familiar comfort foods was so strange it seemed untrue. I was embarrassed. I could not process or understand it. Nothing had prepared me for this. Who was I to face this meal?

A recent collage by Hesselbjerg includes images of chicken embryos. There's also a pair of baby socks with cute cat faces and a cartoon monster leg that seems to be busting out its pants Incredible-Hulk-style. At the bottom of the page is a quote from philosopher and curator Paul B. Preciado, “The monster is one who lives in transition. One whose face, body, and behaviors cannot yet be considered true in a predetermined regime of knowledge and power.” Maybe the monstrous is something still gestating or something we cannot yet completely understand. It's just part of life to encounter monstrosity or to be, for a time, what some might consider a monster.

Hesselbjerg and I spoke on Zoom on July 5, 2023, and edited our conversation after. I was excited to ask him about the interrelationship of his work on paper and his performative culinary experiences—ways of working that seem entwined.

Marcus Civin: Kasper, you just wrapped up, at the start of June, Idiot-Monster Lunch at Nikolaj Kunsthal, the contemporary art center in Copenhagen, Denmark. Can you tell me about this performance/exhibition/meal and how it came about?

Kasper Hesselbjerg: The way I work is building up an archive. I look at a lot of images and collect a lot of them. All of the images come from the internet—this collective image database that we all share, our image reality. I might see an image of a ceramic object that I like a lot, and I think maybe this could relate to something in a text I’m reading or fit into a category of images I’m thinking about. I develop different categories of images that I find interesting. Then, I keep building up the archive—finding more images and more categories until I have these folders full of images. Then, I start printing some of them—more than I need—and putting them on the wall in my studio to see how they relate and work together. That usually leads to even more images and categories. It is a way of renegotiating the relations between images. This work begins before the performative meals and it continues all through that process. Actually putting glue to paper and making a finished collage happens when everything is planned for the performative meal.

MC: I’m looking at one of your recent collages where, in a series of images, you move from the twentieth-century French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s concept of the mirror stage—when infants recognize themselves in their reflection—to a meowing food delivery robot, to a plate of poached and sautéed lamb brains, to the contemporary Hong-Kong-based philosopher Yuk Hui’s concept of cosmotechnics, which, among other things, defines “idiot” as what is “private and pertaining to oneself” and “the monster” as “vulnerable to processes of mutation through contingency and error.” How do you get from Lacan to a robot then lamb brains and cosmotechnics?

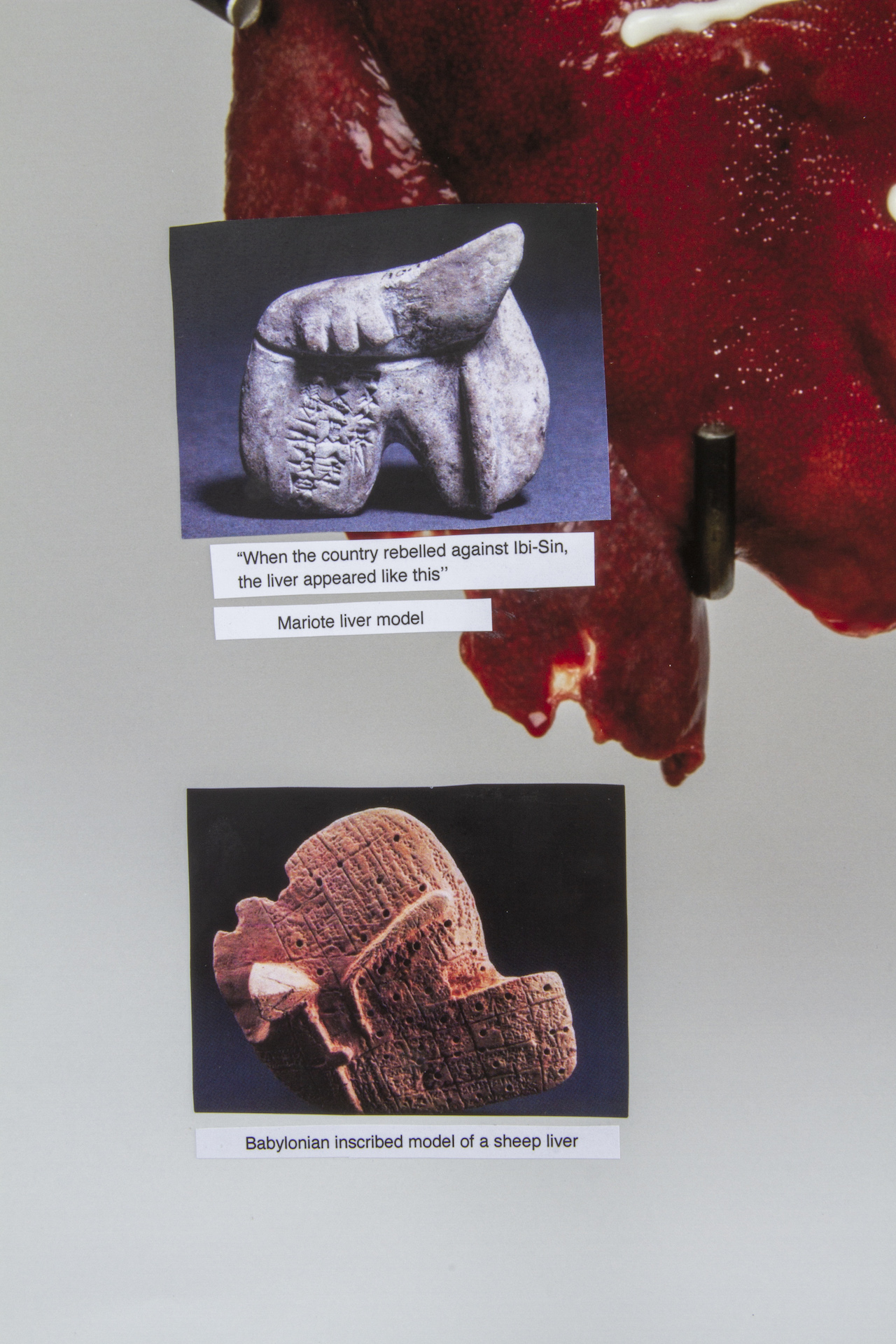

KH: For me, there’s always a question of how much distance there should be between the different images. In the previous collages I did, the relations were more explicit and there were fewer steps between the images. These collages were larger, and there were more images. For this specific collage, all the images refer to notions of the self: recognizing oneself in a mirror as a self-contained entity; the food delivery robot that says “I am here” when bringing/presenting a dish along with the question of what “I” might refer to. In the same way, the sheep’s brain might ask where the self is located. Is it in the liver, as was the common belief before Hippocrates defined the heart as the seat of life? Or in our brain? Or should we look for it in our consuming habits? For Felix Guattari, another psychoanalyst, what capitalism does is produce subjectivity. In between these images or relations, there is mapping to be done, more images to add.

MC: Now, there is more space between the images. You could almost imagine drawing lines between the images to map relationships, but I’m not exactly sure how the lines would go. They might be somehow in that space between images, perhaps making connection points we don't see.

KH: Sometimes there are connections that I’m not aware of or couldn’t explain. It’s not a game of making people lost, but it’s also, for me, interesting to present something with a certain kind of openness.

MC: I wonder: Is there a sly humor behind these collages? Are you interested in humor?

KH: There’s a word in Danish, mærkelig, which means that something arouses wonder by deviating from the normal or from the expected. To mærke means to feel. I think it changed around the Age of Enlightenment, where something that was mærkeligt, something that you could feel, was now considered strange. Sensuous knowledge was not to be trusted. If something is funny, it’s something you feel, not something you understand. I am very interested in both semiotics and affect, how things mean anything to us and how they affect us.

MC: What else happened in the performance? What would I have experienced if I had been lucky enough to be there? What would have made me feel strange and funny?

KH: You would have entered the reception area of the Kunsthal and showed your ticket that you bought in advance. You would have been directed to the gallery. You would have had time to look around. You could have had a look at my collages hung on the wall. Then, you would have been asked to have a seat at a long table. Right after people were seated, the first dish arrived and the waiters presented a brief introduction. So, they would have been like, “This is an oracle egg. It is a marinated egg in tea and different spices. It is served with a chili sauce.”

I was back in the kitchen. I think it’s important for me not to be looking over people experiencing the work. It’s also important for me not to be one of the waiters because my work is not about authenticity. I don’t have to make this. I made the conceptual framework and developed the dishes with a chef, but then the chef prepared them. They don’t have to be made by my hands. After you saw the collages, you would recognize physical elements that would be in the room or on the plates. That cute meowing robot waiter from the collage we discussed was there driving around, helping with the food service.

MC: What are your guiding principles when you are developing dishes? What are your overall structuring techniques for creating a meal?

KH: It’s different from meal to meal. For this meal, most of the dishes were conceptual. Most of them were easily recognizable as a part of the imagery in the collages. So, they were images and sculptures. Making them taste right was secondary. The order of the dishes was also important. It built up. It did have a kind of narrative. For instance, the cracks in the oracle eggs made reference to the I-Ching and reading the future in the cracks in tortoise shells. The second dish was chicken nuggets. First comes the egg and then the chicken. The future of the egg is the nuggets. Or, a chicken is a nugget in the making. At the same time, the meal was about working conditions. Monster Energy Drink was served by delivery people. Five or six delivery people came during both lunches at different points. The first had energy drinks for four people. He gave them out, and then the waiters mixed cocktails using them. Five or ten minutes later, another delivery person with energy drinks for cocktails for other people. The mix for the cocktails included painkillers and allergy medicine. Things to help you cope with the exhaustion of everyday life.

The precarious working conditions of delivery people interest me. These working conditions are advertised as freedom, but really they just constitute precarious work. The way it happens is that the delivery people for the dominant company here, Wolt Delivery, are called partners in the company, but they don’t get health insurance, they don’t get holidays, and they don’t have any power. It somehow resembles the myth of the autonomy and flexibility of the artist, when in reality, the work of most artists (in Denmark) is structured by the rhythm of projects—applications, deadlines, periods of too much work or too little. Another thing that interests me is that, on the delivery app, when I buy food there, the algorithm figures out what I would like to buy next. It predicts my future cravings, or my future meals, before I even think for myself what I would like to eat, and maybe it would be even better at predicting that than I am. And then, there is also something about how everything possible seems to be available. Or rather you can choose anything, as long as it is on Wolt. I was eating in a Thai restaurant where the owner told me that there are a lot of dishes in her restaurant that they’ve stopped offering on Wolt because people complained and thought that they weren’t right because they included fermented crabs or something. These dishes don’t work on Wolt because people aren’t accustomed to their flavor. So, to me, the selection is limited, but restaurants don’t have the option not to present partial versions of their menus on Wolt because it’s such a big part of the market.

MC: This platform is changing the way people think and eat—which reminds me, I want to ask you about the cake that was also part of Idiot-Monster Lunch.

KH: That’s a traditional Danish birthday cake, a cake person. Usually, it’s made for kids. If it was my birthday, maybe my parents would have baked a cake in the shape of a person and it would have had my name on it. I don’t know how the tradition started. I grew up with it, and it’s familiar to everyone in Denmark. You can order these cakes at most bakeries. The figure doesn’t look like you. It’s generic, but it represents you. The one I chose from a bakery looks like a gingerbread man in a way. We celebrate me by eating me, more of me, or something pertaining to me, which seems “idiotic” in the sense that Yuk Hui describes. I gave the bakery a sheep’s liver and asked them to bake it into the cake person. They placed the sheep’s liver in the cake person around where a liver should be and then baked the cake with the liver in it, and that was that. This inlaid liver made the cake a bit monstrous. A waitress opened it up, carving out the sheep’s liver, referencing how the Etruscans, the Mariotes, and the Babylonians would take out a sheep’s liver and read the future in it.

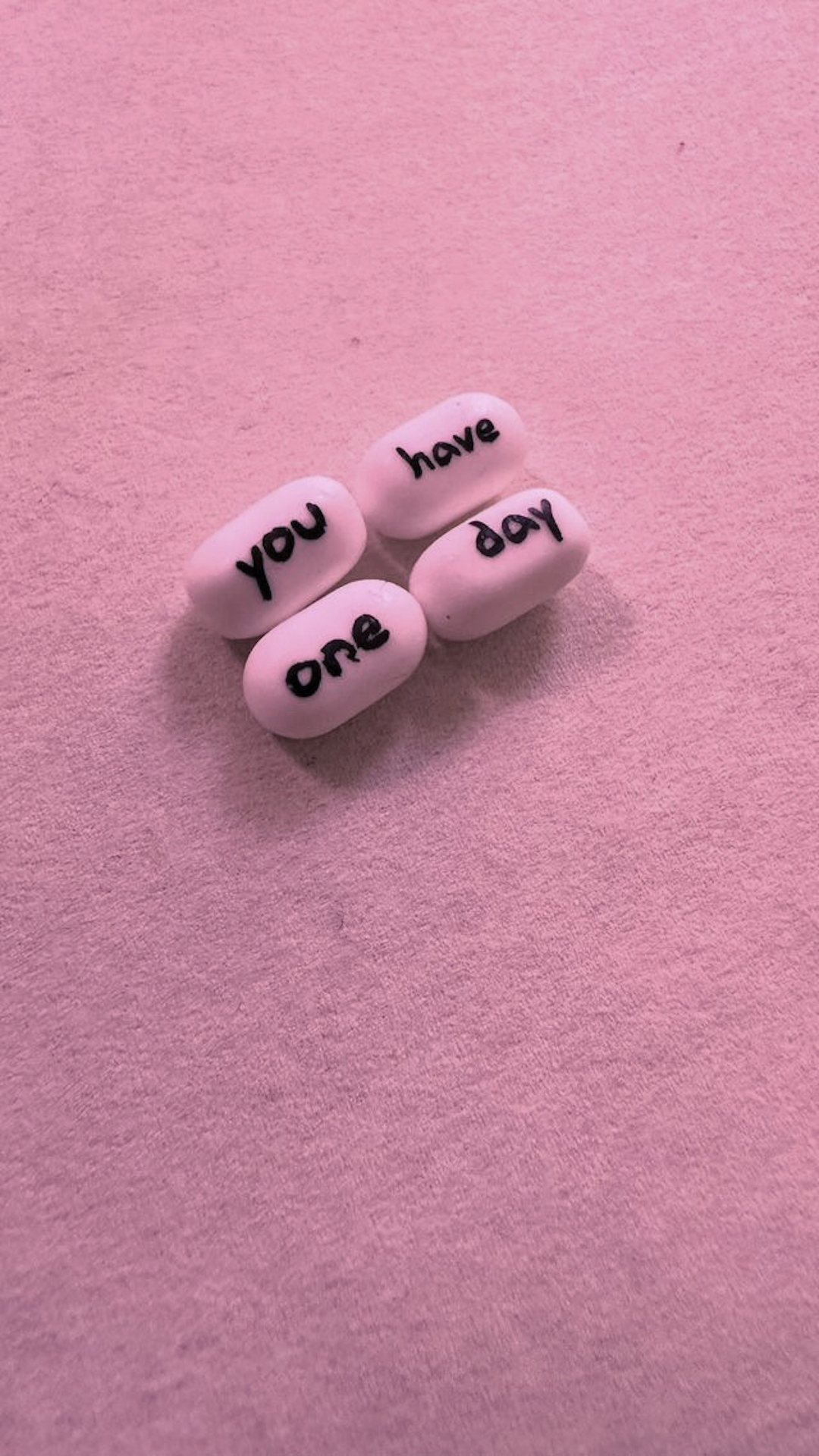

The meal ended with Tic Tacs I’d bought with messages printed on them. The box said, “You mint a lot to me,” or something like that. In the same way that you could look at that tortoise shell and ask it something, read it, and it would give you an answer, you could ask the sheep's liver. You could also ask your Tic Tac. In the end, after eating the cake, the waiters gave guests three or four Tic Tacs and encouraged them to ask the candy something, then see what was printed there as the response.

MC: Over the course of the meal, you ate the egg and then the chicken nuggets, so you had something filling. Then there was this rush of sugar and caffeine from the cake and the energy drink, but the medicine would maybe make you tired. In this way, you are pulled in different directions simultaneously. You’re up. You’re down. You don’t know, are you high or low?

KH: Caffeine and sugar are such important ingredients in contemporary eating, and I think they take up a lot of room in many people’s diets. I might be sensitive, but to me, an energy drink is a wild experience in itself. It makes me tingle.

MC: As we’ve been talking, I’ve been eating blueberries and drinking a fizzy, sour probiotic drink. It’s a strange experience. The drink and the berries don’t go well together, maybe because the drink is much more sour than I expected. I think I’m getting a sense of what you’re after in your work with the food experience I’m having right now. It’s a strange experience.

KH: When you eat blueberries, you are part of this functional food discourse. It’s interesting being aware of what is very physical and tangible—something you experience with your body, something that links you to nature and the world. Food goes through you. At the same time, you are connecting to a food discourse that makes eating very symbolic. It’s obvious that you experience food with your senses, and no one can do that for you. No one else can experience that fizziness and sourness of your drink in your body. At the same time, that personal experience is linked to a cultural level that influences how you evaluate that exact concrete experience. So, this is what “healthy,” “classy,” or “sophisticated” tastes and feels like.

MC: I think about my relationship to consumption in general. I feel good if I go to a nice restaurant or if my refrigerator is well-stocked.

KH: It’s a big theme of my work: modes of consumption and consuming your idea of yourself. I have a collection of advertisements where animal characters suggest you eat parts of them—a pig advertising sausages or spare ribs, a chicken advertising eggs. Is it called opportunism in English? There’s something opportunistic about selling your friends as food, regardless of principle. That’s a capitalistic, very crude mode.

You go to a restaurant to be the person who eats at this restaurant and experience yourself while you’re at the restaurant. So, you share your experience on social media, and it’s not so much about eating the food at the restaurant as it is about experiencing you being a person at this restaurant. One of the things I’m doing at the moment is trying to suggest reading capitalism as a cosmology—something that we live within where it’s difficult to imagine something outside. You cannot leave it, but you can work to create a distance from its power and influence to establish some micro-discourses where a different logic applies and answers to other kinds of value that you are developing yourself or with friends or a community.

About the Artist

Kasper Hesselbjerg was born in 1985, and currently lives and works in Vanløse. He graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 2013. For several years he has been working with sculptures, collage, and language in the pursuit of questions on the meaning of objects and its effect on daily lives. Besides gallery and museum shows, he has produced a series of exhibitions in the format of dinners consisting of edible sculptures for the guests to consume. His latest published book is Recipe for Snails and Success that combines classic French cooking with traditional Chinese medicine in order to show different “cosmological” relations to what human eat. He is also the founder and editor of the publishing house emancipa(t/ss)ionsfrugten with Absalon Kirkeby.

Hesselbjerg received several grants of honor, including: Carl Nielsen og Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen Legatets Talent Award (2021), Klara Karolines Fond found by Aase & Poul Gernes (2019), Niels Wessel Bagges Kunstfond (2018), Sven Dalsgaards Grant (2018), Ole Haslunds Kunstnerfond (2018), Schadeprisen (2016), Astrid Noacks Grant (2015), and Fr. Gerda Jensens kunstnerlegat (2013). He has previously been an artist-in-residency in Paris, New York, Scala (Italy), Qingyun (China), and Beijing.

About the Writer

Marcus Civin writes about art and artists. He has also written poems for walls, doors, and windows, and is working on a series of love poems called ONLY POEMS that consist of four, four-letter words—one of which is the word ONLY. Other conversations with artists have appeared recently in BOMB, Maake, Afterimage, and Damn.